The IPHC’s current understanding of juvenile Pacific halibut migration is the result of a variety of information sources including occurrence data from NOAA Fisheries, IPHC Fishery-Independent Setline Surveys (FISS) and tagging projects that span several decades. The IPHC recently reviewed the last 100 years of migration research available for Pacific halibut, with a focus on tagging experiments and presented a conceptual model of seasonal migrations from larval to adult life history stages than spans the entire distribution range of the species in the North Pacific Ocean (Carpi et al. 2021). Specific details on the different types of juvenile migration of Pacific halibut can be found in the following sections.

Distribution of early life stages

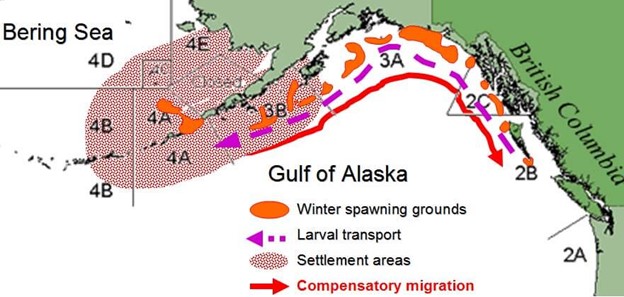

Pacific halibut spawn along the continental shelf edge and embryos and larvae are carried away from the spawning grounds by prevailing currents flowing westward in the Gulf of Alaska, and north and west in the Bering Sea. Pelagic larvae depend on currents to transport them to areas of plankton production where they are able to feed, and eventually settle inshore in shallow nursery areas. Juvenile Pacific halibut begin migrating from the nursery areas within a year or two of settlement in a direction counter to the currents that transported them there, i.e. to the east and south in the Gulf of Alaska and to the south, north, and west in the Bering Sea (Fig. 1). They also disperse to greater depths as they age. A broader conceptual model of juvenile Pacific halibut movement in the North Pacific Ocean was recently generated (Carpi et al. ,2021).

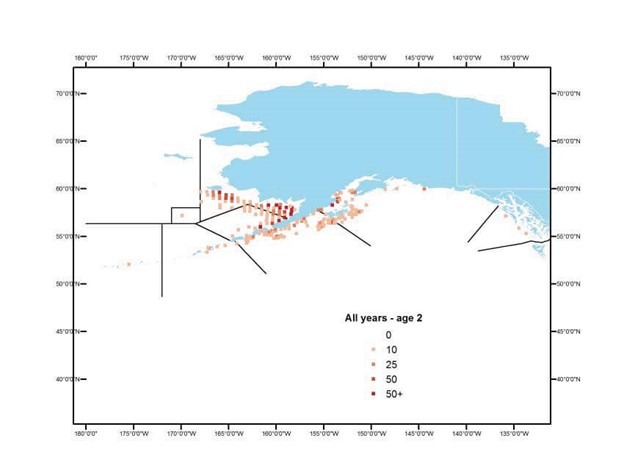

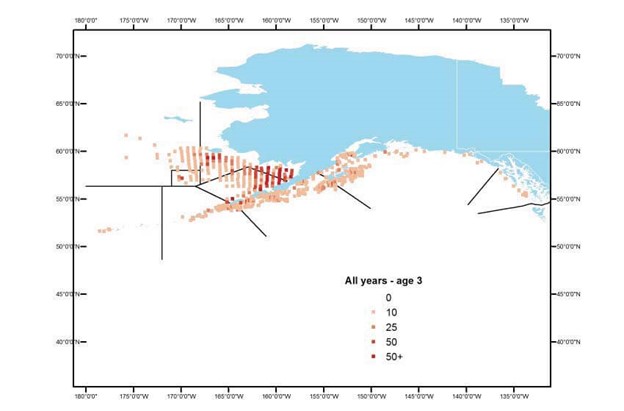

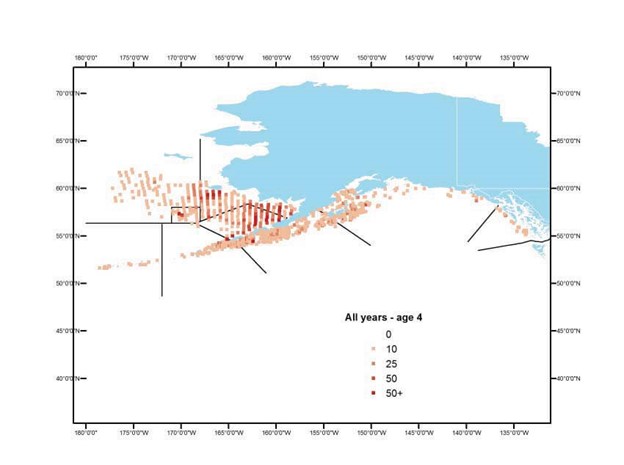

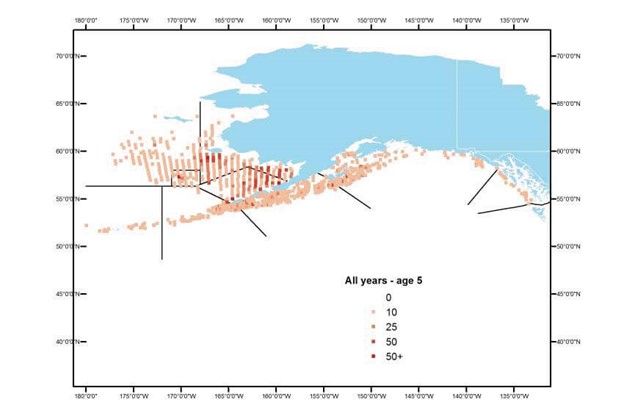

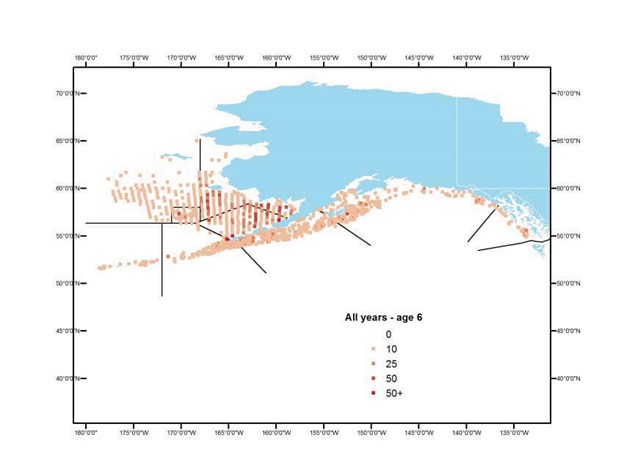

Pacific halibut are observed as embryos and larvae in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration ichthyoplankton surveys, but are essentially invisible in their typical flatfish form to any survey gear until they become vulnerable to the NMFS groundfish trawl survey gear at 15-20 cm fork length or at 1-2 years of age. The incidence of Pacific halibut in aggregate that have been caught during the NOAA Fisheries trawl surveys since the 1980s can be seen in Figures 2-6. While the largest numbers of juvenile Pacific halibut continue to be detected on or near nursery grounds (around Kodiak Island and inner Bristol Bay), it is clear that a portion of juveniles begin to disperse at ages as young as 2 years old. Three-year-old Pacific halibut are found in small numbers in the central Gulf and southern Bristol Bay, and 4-year old Pacific halibut are found throughout the Gulf of Alaska and into the Aleutian Islands. Five- and 6-year-old Pacific halibut are found in greater numbers coastwide and at greater depths throughout their known range.

Figure 2. Distribution of age-2 halibut caught aboard the NMFS groundfish trawl surveys. Shaded squares indicate numbers caught per station.

Figure 3. Distribution of age-3 halibut caught aboard the NMFS groundfi sh trawl surveys. Shaded squares indicate numbers caught per station

Figure 3. Distribution of age-3 halibut caught aboard the NMFS groundfi sh trawl surveys. Shaded squares indicate numbers caught per station

Figure 4. Distribution of age-4 halibut caught aboard the NMFS groundfi sh trawl surveys. Shaded squares indicate numbers caught per station.

Figure 5. Distribution of age-5 halibut caught aboard the NMFS groundfi sh trawl surveys. Shaded squares indicate numbers caught per station.

Figure 6. Distribution of age-6 halibut caught aboard the NMFS groundfi sh trawl surveys. Shaded squares indicate numbers caught per station.

Juvenile migration patterns

Most of the knowledge of juvenile migration patterns for Pacific halibut originates from traditional tagging (external tags) conducted between 1963 and 1986. A formal tag-recapture analysis of migration rates for juvenile Pacific halibut resulted from the peak tagging years of 1980 and 1981 (67,000 juveniles) and produced estimates of migration rates between IPHC Regulatory Areas 2 and 3 (Hilborn et al. 1995). Although no formal tag-recapture analysis was available for juveniles < 65 cm in length tagged in Area 4, between 20% and 30% of juveniles tagged in Area 4 were recaptured outside of the area. Raw recovery proportions for Pacific halibut from 2 to 6 years of age and for Pacific halibut < 65 cm in length at the time of tagging are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. For Pacific halibut < 82 cm in length, between 50% to 60% of tag releases occurred in the proximity of the Aleutian Islands between Unimak Island and Unalaska Island, with the remaining releases being found spread along the Bering Sea edge, flats, and the Bering Sea Closed Area. Table 3 shows recovery proportions and total numbers of Pacific halibut of < 65 cm in length, when dividing the combined Area 4 into Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska components. Area 4 migration rate estimates are available for Pacific halibut of 65 to 80 cm in length (Deriso et al. 1983) and suggest very similar emigration rates (around 23%) for IPHC Regulatory Area 4 and Area 3B, although they do not differentiate between Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska components.

Table 1. Raw recovery rates of externally-tagged Pacific halibut ages 2 to 6 tagged in IPHC Regulatory Area 4 (from Clark and Hare, 1998).

| Recovery Area | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 3 | 2C | 2B | 2A |

| 0.704 | 0.177 | 0.038 | 0.062 | 0.020 |

Table 2. Raw recovery rates of externally-tagged Pacific halibut < 65cm in length at the time of tagging in IPHC Regulatory Area 4, summarized from IPHC database.

| Recovery Area | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 3 | 2C | 2B | 2A |

| 0.763 | 0.142 | 0.027 | 0.050 | 0.018 |

Table 3. Recovery proportions by release and recovery areas of externally-tagged Pacific halibut < 65 cm in length at the time of tagging. Total numbers are provided in the last column. IPHC Regulatory Area 4 is presented as separate Bering Sea (BS) and Gulf of Alaska (GOA) components. The values in bold represent the proportion that was both released and recovered in the same area.

| Release Area | Recovery Area | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 BS | 4 GOA | 3B | 3A | 2C | 2B | 2A | Total recovered | |

| 4 BS | 0.748 | 0.047 | 0.038 | 0.085 | 0.011 | 0.049 | 0.021 | 527 |

| 4 GOA | 0.225 | 0.250 | 0.100 | 0.275 | 0.025 | 0.125 | – | 40 |

| 3B | 0.014 | 0.007 | 0.452 | 0.290 | 0.071 | 0.148 | 0.017 | 714 |

| 3A | 0.001 | – | 0.020 | 0.699 | 0.063 | 0.192 | 0.025 | 1,625 |

| 2C | – | – | – | 0.022 | 0.816 | 0.160 | 0.002 | 463 |

| 2B | – | 0.000 | – | 0.004 | 0.025 | 0.967 | 0.005 | 3,077 |

| 2A | – | – | – | 0.053 | – | 0.105 | 0.842 | 19 |

| 6,465 | ||||||||

The IPHC conducted a large-scale Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT) tagging effort in the mid-2000s. The strength of this type of tag was that it was detectable only by specialized equipment used by IPHC samplers, and thus alleviated the reporting bias inherent in external tagging. The tags were placed during the IPHC fishery-independent setline survey and did not specifically target juvenile Pacific halibut, but a component of fish caught during the surveys are < 82 cm in length and, therefore, results of the project allowed the calculated estimated probabilities of movement based on length.

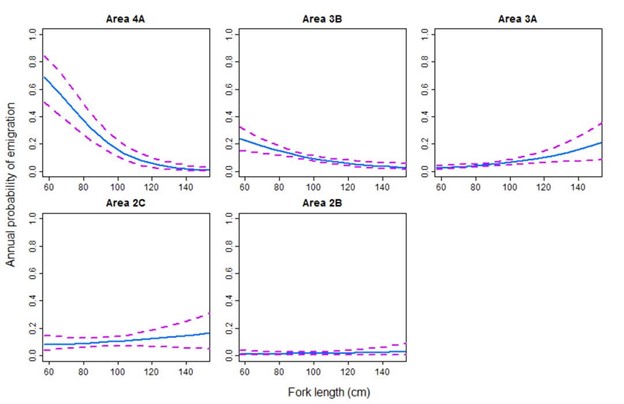

For western areas, the estimated probability that a fish migrates in a given year declines with increasing length. Estimated annual emigration probabilities are very high for smaller IPHC Regulatory Area 4A fish, over 0.5 per year for Pacific halibut < 70 cm in length, and remaining over 0.2 for fish up to 95 cm in length. For Area 3B, Pacific halibut < 80 cm in length have at least a 0.15 probability of moving each year, a rate that declines with increasing length. For Areas 2B, 2C, and 3A, the relationship between emigration rates and fish length is less clear (Fig. 7). [Primary source: Webster et al. (2013)]

Figure 7. Estimated relationship between annual emigration probability and Pacific halibut length from modelling of the PIT tag data. Dashed lines are upper and lower 95% Bayesian credible interval bounds.

Migration between ocean basins

Data from Bering Sea tagging programs show that Pacific halibut < 65 cm in length have historically had high rates of movement into the Gulf of Alaska: depending on the release area: 70-90% of tagged Pacific halibut were recovered in the Gulf of Alaska after eight or more years following release. While the general pattern was for a south and eastward movement across the Gulf of Alaska, there was also some migration of small Pacific halibut to the west, towards IPHC Regulatory Area 4B for all release regions. Studies tagging larger fish have found much less movement into or out of IPHC Regulatory Area 4B than other regulatory areas, but these data provide evidence that the population in IPHC Regulatory Area 4B is connected with that in the eastern Bering Sea through the westward movement of juvenile fish.

While the raw data provide evidence that juvenile Pacific halibut tagged in the Bering Sea have, over a period of several years, high rates of migration into the Gulf of Alaska, the juvenile tagging studies were never designed with the goal of producing statistically sound estimates of migration rates. Low recovery rates for the most consistent grid design, high recovery rates resulting from unrepresentative sampling, and the lack of a consistent, contemporaneous tagging program in the Gulf of Alaska make these data unsuitable for formal statistical modelling. The data do show that a few years after release, a majority of the recovered tagged Pacific halibut are found in the Gulf of Alaska. However, it is also likely that a greater intensity of longline fishing in the Gulf of Alaska than in the Bering Sea leads to tagged fish that move to the Gulf of Alaska to more likely be recovered than those that remain within the Bering Sea. Raw out-of-region recovery rates suggest higher annual movement rates than expected. Even if we overlook the shortcomings of the design, an estimate of annual movement rates cannot be derived without additional information on the relative probabilities of tag recovery in the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska. . Overall, the conducted tagging studies suggested only broad-scale movement pathways from the Bering Sea to the Gulf of Alaska (Webster et al., 2013). More recent studies based on spatio-temporal modeling of demersal Pacific halibut (Webster et al., 2020) have provided support for the existence of migratory pathways from settlement grounds in the southeastern Bering Sea to the Gulf of Alaska for juvenile Pacific halibut between 4 and 6 years of age (Sadorus et al., 2021).

References

Carpi, P., Loher, T., Sadorus, L.L, Forsberg, J.E., Webster, R.A., Planas, J.V, Jasonowicz, A., Stewart, I.J, and Hicks, A.C. 2021. Ontogenetic and spawning migration of Pacific halibut: a review. Rev Fish Biol Fisheries. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-021-09672-w

Clark, W. G. and Hare, S. R. 1998. Accounting for bycatch in management of the Pacific halibut fishery. N. Am. J. Fish. Mgmt. 18:809-821.

Deriso, R. B. and Quinn II, T. J. 1983. The Pacific halibut resource and fishery in regulatory Area 2: II Estimates of biomass, surplus production, and reproductive value. Int. Pac. Halibut Comm. Sci. Rep. 67.

Hilborn, R., Skalski, J., Anganuzzi, A. and Hoffman, A. 1995. Movements of juvenile halibut in IPHC regulatory areas 2 and 3. Int. Pac. Halibut Comm. Tech. Rep. 31.

Sadorus, L.L., Goldstein, E.D., Webster, R.A., Stockhausen, W.T., Planas, J.V., Duffy-Anderson, J.T. (2021) Multiple life-stage connectivity of Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) across the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska. Fish. Oceanogr. Vol. 30(2):174-193. doi.org/10.1111/fog.12512

Webster, R. A., Clark, W. G., Leaman, B. M., and Forsberg, J. E. 2013. Pacific halibut on the move: a renewed understanding of adult migration from a coastwide tagging study. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 70: 642-653.

Webster, R.A., Soderlund, E., Dykstra, C.L., and Stewart, I.J. (2020) Monitoring change in a dynamic environment: spatio-temporal modelling of calibrated data from different types of fisheries surveys of Pacific halibut. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 77: 1421-1432. doi.org/10.1139/cjfas-2019-0240

Additional sources of information

Best, E. A. 1969. Recruitment investigations: Trawl catch records Bering Sea, 1967. Int. Pac. Halibut Comm. Tech. Rep. 1.

Best, E. A. 1969. Recruitment investigations: Trawl catch records Gulf of Alaska, 1967. Int. Pac. Halibut Comm. Tech. Rep. 2.

Best, E. A. 1969. Recruitment investigations: Trawl catch records Eastern Bering Sea, 1968 and 1969. Int. Pac. Halibut Comm. Tech. Rep. 3.

Best, E. A. 1969. Recruitment investigations: Trawl catch records Gulf of Alaska, 1968 and 1969. Int. Pac. Halibut Comm. Tech. Rep. 5.

Best, E. A. 1970. Recruitment investigations: Trawl catch records Eastern Bering Sea, 1963, 1965,and 1966. Int. Pac. Halibut Comm. Tech. Rep. 7.

Best, E. A. 1974. Juvenile halibut in the eastern Bering Sea: Trawl surveys, 1970-1972. Int. Pac. Halibut Comm. Tech. Rep. 11.

Best, E. A. 1974. Juvenile halibut in the Gulf of Alaska: Trawl surveys, 1970-1972. Int. Pac. Halibut Comm. Tech. Rep. 12.

Best, E. A. 1977. Distribution and abundance of juvenile halibut in the southeastern Bering Sea. Int. Pac. Halibut Comm. Sci. Rep. 62.

Best, E. A. and Hardman, W. H. 1982. Juvenile halibut surveys, 1973-1980. Int. Pac. Halibut Comm. Tech. Rep. 20.