Economic Research

Under the Convention (Article III), the IPHC’s mandate is optimum management of the Pacific halibut resource, which necessarily includes an economic dimension. Fisheries economics is an active field of research around the world in support of fisheries policy and management. Adding the economic expertise to the Secretariat, the IPHC has become the first regional fishery management organization (RFMO) in the world to do so.

The goal of the IPHC economic study is to:

Provide stakeholders with an accurate and all-sectors-encompassing assessment of the socioeconomic impact of the Pacific halibut resource that includes the full scope of Pacific halibut’s contribution to regional economies of Canada and the United States of America.

Document

Title

To that end, the Secretariat in collaboration with stakeholders through survey participation developed the Pacific Halibut multiregional economic impact assessment (PHMEIA) with an intention to:

- define the economic importance of the Pacific halibut resource and fisheries at the community, regional, and national levels;

- contribute to a wholesome approach to Pacific halibut management that is optimal from both biological and socioeconomic perspective.

Check our Pacific halibut economic impact visualization tool for the most up-to-date economic impact estimates. The use of the application can be guided by the PHMEIA app manual.

Economic Impact Assessment – what is it?

Fisheries management policies that alter catch limits have a direct impact on commercial harvesters, but at the same time, there is a ripple effect through the economy. The PHMEIA assesses three economic impact (EI) components pertaining to Pacific halibut.

- Direct EIs reflect the changes realized by the direct Pacific halibut resource stock users (fishers, charter business owners), as well as the forward-linked Pacific halibut processing sector (i.e., EI related to downstream economic activities).

- Indirect EIs are the result of business-to-business transactions indirectly caused by the direct EIs. The indirect EIs provide an estimate of the changes related to expenditures on goods and services used in the production process of the directly impacted industries. In the context of the PHMEIA, this includes an impact on upstream economic activities associated with supplying intermediate inputs to the direct users of the Pacific halibut resource stock, for example, impact on the vessel repair and maintenance sector or gear suppliers.

- Finally, induced EIs result from increased personal income caused by the direct and indirect effects. In the context of the PHMEIA, this includes economic activity generated by households spending earnings that rely on the Pacific halibut resource, both directly and indirectly.

The economic impact is most commonly expressed in terms of output, that is the total production linked (also indirectly) to the evaluated sector. PHMEIA also provides estimates using several other metrics, including compensation of employees, contribution to the gross domestic product (GDP), employment opportunities, and households’ prosperity (income by place of residence).

The model also accounts for interregional spillovers, which accommodate an increasing economic interdependence of regions and nations. Economic impact of Pacific halibut is not necessarily limited to where it is fished or processed. Economic benefits from the primary area of the resource extraction are leaked when inputs to production are imported, when wages earned by nonresidents are spent outside the place of employment, or when earnings from quota holdings flow to nonresident beneficial owners. At the same time, there is an inflow of economic benefits to the local economies from when products are exported, or services are offered to non-residents.

The study offers the first multiregional economic impact analysis tracing the transmission of economic impacts originating from the fisheries sectors internationally. It consistently estimates both backward-linked (related to inputs) and forward-linked (input-dependent) effects related to commercial and recreational (both guided/charter and unguided) Pacific halibut sectors. Moreover, the study currently details the geography of impacts in Alaska, paying particular attention to quantifying leakage of economic benefits from regions strongly dependent on fisheries, addressing the Commission’s interest in community impacts.

Why did the IPHC undertake an economic analysis?

PHMEIA is a core product of the IPHC socioeconomic program that directly responded to the Commission’s “desire for more comprehensive economic information to support the overall management of the Pacific halibut resource in fulfillment of its mandate” (economic study terms of reference). Moreover, socioeconomic objectives are prevalent in the legislation of Canada and the United States.

Federal laws governing US marine fisheries require assessing any proposed fishery management action in terms of its regional or community economic impacts. These laws include, among others, the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA, amended on January 12, 2007), National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and Executive Order 12866. For example, the National Standard 8, one of the principles mandated by the MSA, requires that while the conservation and management measures must be consistent with the conservation requirements, they must also account for “the importance of fishery resources to fishing communities” and “to the extent practicable, minimize adverse economic impacts on such communities” (Section 301[a]8). It implies that fishery managers, when considering any action, must take into account the economic impact on various stakeholder groups, including fishers, but also processors and fishing-dependent communities. The MSA also establishes Regional Fishery Management Councils, which role is to develop fisheries management plans that “take into account the social and economic needs of the States” while working on the stewardship of fishery resources. Lately, NOAA recommended routine consideration of socioeconomic drivers in the fisheries stock assessment process (Next Generation Stock Assessment framework).

The document establishing national fisheries policy in Canada for the modern era is the 1976 Policy for Canada’s Commercial Fisheries. It states that “the guiding principle in fishery management no longer would be maximization of the crop sustainable over time but the best use of society’s resources.” The “best use” is defined as “the sum of net social benefits (personal income, occupational opportunity, consumer satisfaction and so on) derived from the fisheries and the industries linked to them” (Fisheries Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. F-14). These objectives have been affirmed in legislation (Oceans Act, S.C. 1996, c.31), according to which fisheries are expected to be managed to meet a full spectrum of social and economic objectives. More recently, the commitment to the sustainability of fisheries – “as a vital part of our [Canada’s] food supply, as well as an important source of jobs and economic activity for coastal communities” – has been reaffirmed in the Government Response to the report West Coast Fisheries: Sharing Risks and Benefits by the Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans from July 8, 2020.

What is Included in the model?

COMMERCIAL SECTOR

The economic effects of changes to harvest levels can be far-reaching. Fisheries management policies that alter catch limits have a direct impact on commercial harvesters, but at the same time, there is a ripple effect through the economy.

Backward-linked sectors are industries that supply commercial fishing vessels with inputs. These sectors rely on this demand when making decisions related to their production levels and expenditure patterns. For example, vessels making more fishing trips purchase more fuel and leave more money in a local grocery store that supplies crew members’ provisions. More vessel activity means more business to vessel repair and maintenance sector or gear suppliers. An increase in landings also brings more employment opportunities, and, as a result, more income from wages is in circulation. When spending their incomes, local households support local economic activity that is indispensable to coastal communities’ prosperity.

Forward-linked sectors are industries that rely on fish supply. Changes in the domestic fisheries output, unless fully substituted by imports, are also associated with production adjustments by industries relying on fish supply, such as seafood processors. These changes also affect suppliers to the forward-linked sectors, creating additional ripple effect.

While the complete path of commercially landed fish includes, besides harvesters and processors, also seafood wholesalers and retailers, and services when it is served in restaurants, it is important to note that there are many seafood substitutes available to buyers. Thus, including economic impacts beyond wholesale in PHMEIA, as opposed to assessing the snapshot contribution to the gross domestic product (GDP) along its entire value chain, would be misleading when considering that it is unlikely that supply shortage would result in a noticeable change in retail or services level gross revenues (Steinback and Thunberg 2006). Supplementary snapshot assessment of Pacific halibut contribution to the GDP along the entire value chain, from the hook-to-plate, accounting for the trade balance, is available in IPHC-2021-ECON-06-R01.

The figure below summarizes the impacts considered when analyzing commercial harvesters as users of the Pacific halibut resource.

RECREATIONAL SECTOR

Economic impacts are also attributed to recreational fishing activities. By running their businesses, charter operators create demand for fuel, bait fish, boat equipment, and fishing trip provisions. They also create employment opportunities and generate incomes that, when spent locally, support various local businesses. Pacific halibut will also support angling-dependent services, for example, hospitality services in case of fly-in lodges that specialize in serving customers interested in Pacific halibut fishing.

What is more, anglers themselves contribute to the economy by creating demand for goods and services related to their fishing trips. This includes expenses related to the travel that would otherwise not be incurred (e.g., auto rental, fuel cost, lodging, food, site access fees), as well as money spent on durable goods that are associated with recreational fishing activity, e.g., rods, tackle, outdoor gear, boat purchase, and applies to both guided and unguided recreational fishing.

The figure below summarizes the impacts of Pacific halibut recreational fishing on the economy considered in the extended PHMEIA-r model.

ECONOMIC IMPACT OF SUBSISTENCE FISHING

Previous research suggested that noncommercial or nonmarket-oriented fisheries’ contribution to national GDP is often grossly underestimated, particularly in developing countries (e.g., Zeller, Booth, and Pauly 2006). Subsistence fishing is also important in traditional economies, often built around indigenous communities. Wolfe and Walker (1987) found that there is a significant relationship between the percentage of the native population in the community and reliance on wildlife as a food source in Alaska. However, no comprehensive assessment of the economic contribution of the subsistence fisheries to the Pacific northwest is available. The only identified study, published in 2000 by Wolfe (2000), suggests that the replacement value of the wild food harvests in rural Alaska may be between 131.1 and 218.6 million dollars, but it does not distinguish between different resources and assumes equal replacement expense per lb. Aslaksen et al. (2008) proposed an updated estimate for 2008 based on the same volume, noting that transportation and food prices have risen significantly between 2000 and 2008, and USD 7 a pound is a more realistic replacement value. This gives the total value of USD 306 million, but the approach relies upon the existence of a like-for-like replacement food (in terms of taste and nutritional value), which is arguably difficult to accept in many cases (Haener et al. 2001) and ignores the deep cultural and traditional context of the Pacific halibut in particular (Wolfe 2002). A more recent study by Krieg, Holen, and Koster (2009) suggests that some communities may be particularly dependent on wildlife, consuming annually up to 899 lbs per person, but no monetary estimates are derived. Moreover, although previous research points to the presence of sharing and bartering behavior that occurs in many communities (Szymkowiak and Kasperski 2020; Wolfe 2002), the economic and cultural values of these networks have yet to be thoroughly explored.

The subsistence component of the study is a subject of a collaborative project with NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Center: Fish, Food, and Fun – Exploring the Nexus of Subsistence, Personal Use, and Recreational Fisheries in Alaska (SPURF project).

MORE ON MODEL DEVELOPMENT

Document IPHC-2021-ECON-01 reviews relevant economic impact assessment studies focused on the fisheries sector. Document IPHC-2021-ECON-02-R02 provides a compendium of fisheries-related economic statistics used in the model. Document IPHC-2021-ECON-03 contains the methodological annex, while IPHC-2021-ECON-07 provides details on the model setup.

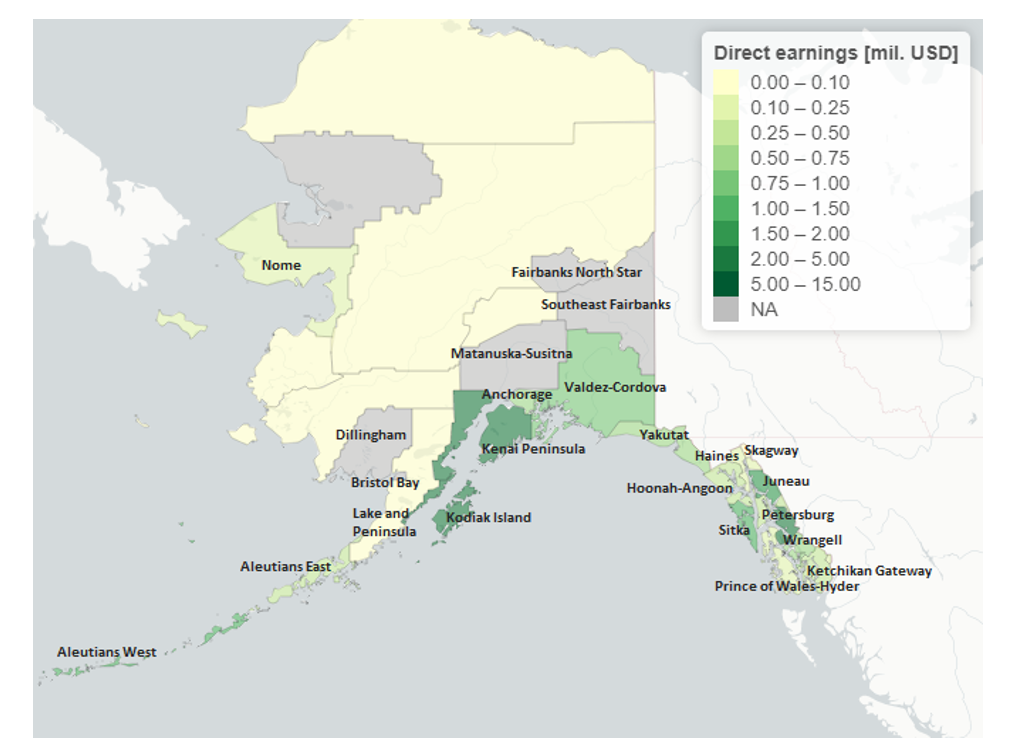

Model results

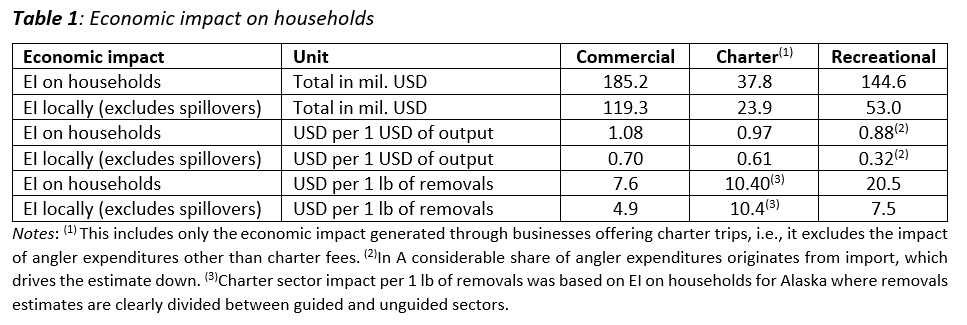

The model results suggest that Pacific halibut commercial fishing’s total estimated impact in 2019 amounts to USD 195.9 mil. (CAD 259.9 mil.) in households’ earnings, including an estimated USD 58.3 mil (CAD 77.3 mil) in direct earnings in the Pacific halibut fishing sectors and USD 11.9 mil. (CAD 15.8 mil.) in the processing sector, and USD 185.2 mil (CAD 245.7 mil.) in household income (Table 1).

The total contribution of the Pacific halibut charter sector to household income is assessed at USD 37.8 mil. for 2019. Accounting for angler expenditures adds another USD 106.8 mil. (CAD 141.7 mil.) to the economic impact of the recreational sector. This translates into 11% less per 1 USD of output for the charter sector and 19% less for the recreational sector overall in comparison with the commercial sector. This is not surprising since the commercial sector’s production supports not only suppliers to the harvesting sector, but also the forward-linked processing sector (thus, also households employed by these sectors). Recreational sector results, on the other hand, to a large degree are driven by expenditures on goods that are often imported, consequently supporting households elsewhere.

A somewhat different picture emerges when comparing EI per pound of Pacific halibut removal counted against TAC in the stock assessment. This measure is 37% higher for the charter sector, and 170% higher for the recreational sector overall when compared with the commercial sector. These differences, however, are less pronounced when focusing only on the EI retained within the harvest region.

It should also be noted, however, that this analysis should not be used as an argument in sectoral allocations discussions because, as a snapshot analysis, it does not reflect the implications of shifting supply-demand balance. Participation in sport fishing do not typically scale in a linear fashion with changes to harvest limits.

PHMEIA model also informs on the economic impact by county (currently limited to Alaska), highlighting regions where communities may be particularly vulnerable to changes in the access to the Pacific halibut resource. In 2019, from USD 28.9 mil. of direct earnings from Pacific halibut commercial sectors in Alaska, 71% was retained in Alaska. These earnings were unevenly distributed between Alaskan counties, as shown in the map below (Figure 1). The most direct earnings per dollar landed are estimated for Ketchikan Gateway, Petersburg, and Sitka countries, while the least for Aleutians East, Yakutat, and Aleutians West counties. Low earnings per 1 USD of Pacific halibut landed in the county are a result of the outflow of earnings related to vessels’ home base, vessels’ ownership, and quota ownership, processing locations, and processing companies’ ownership.

Notes: Alaska retains 71% of direct earnings within the state.

Figure 1. County-level estimates of direct earnings in the Pacific halibut commercial sectors in Alaska in 2019.

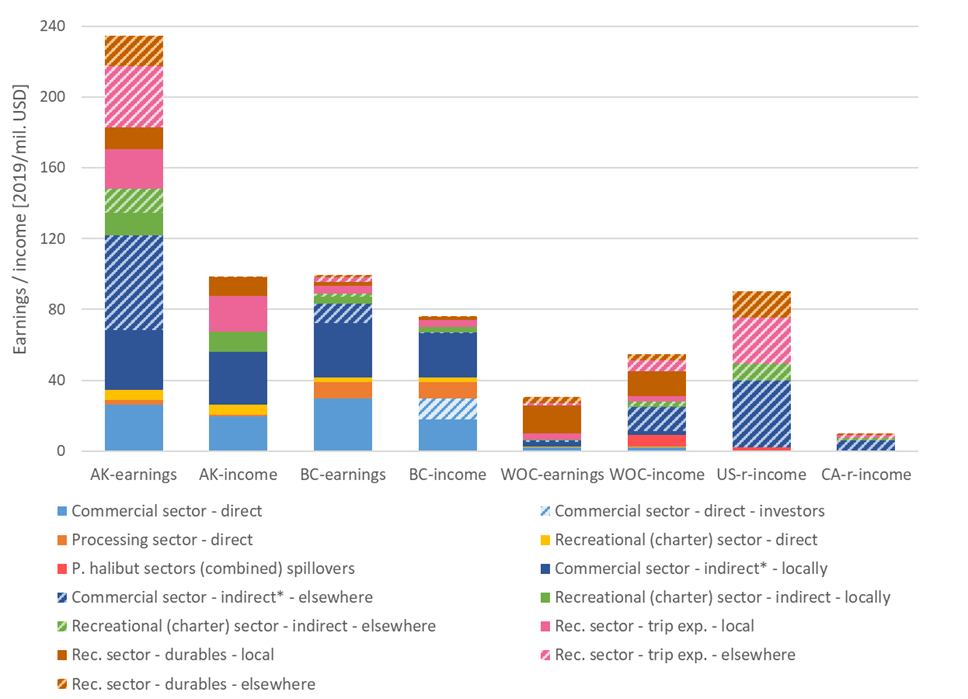

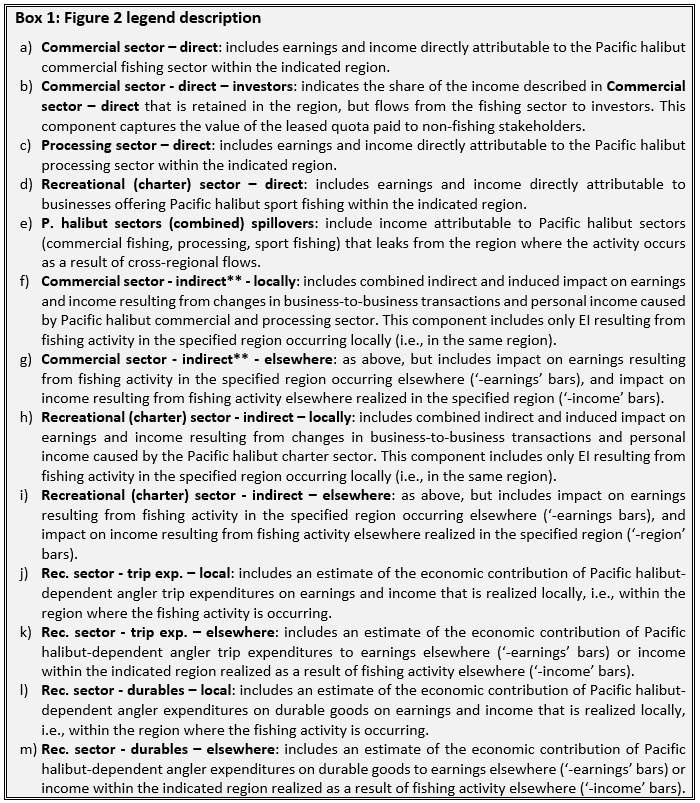

Figure 2 depicts the impact of Pacific halibut commercial and recreational fishing on household earnings and income, highlighting the importance of considering cross-regional flows related to Pacific halibut. Earnings estimates (bars with ‘-earnings’ suffix) summarize economic impact by place of work (i.e., where the fishing activity occurs). Income estimates (bars with ‘-income’ suffix) reflect earnings after adjustments for cross-regional flows, i.e., provide estimates by the place of residence of workers, business owners, or owners of production factors (i.e., quota or permit owners).

Notes: Legend description available in Box 1. Figure omits the impact on ROW (marginal). *Commercial indirect effects include processing.

Figure 2. Pacific halibut impact on household earnings and income (2019).

It is important to note that the model continues to rely heavily on secondary data sources such as NOAA or DFO surveys that did not necessarily target specifically Pacific halibut users or were not collected annually. As such, the model results are conditional on the adopted assumptions for the components for which data inputs were imputed or derived from broader scope surveys (details on data inputs are available in IPHC-2021-ECON-02-R02). That said, the Secretariat strives to make the best use of data collection programs of national and regional agencies, academic publications on the topic, and grey literature reporting on fisheries in Canada and the United States.

ECONOMIC IMPACT VISUALIZATION TOOL

The section on PHMEIA and PHMEIA-r results focuses on the economic impact on households as the most meaningful metric to the general population. However, as noted in the introduction, the economic impact can be expressed with various other metrics, and derived for just a subset of sectors. Regulators and stakeholders may also be interested in assessing various combinations of regional allocations of mortality limits. Thus, the PHMEIA and PHMEIA-r are accompanied by the economic impact visualization tool designed to display the full set of model results.

The updated app also translates regional economic impacts to county-level estimates based on changes in harvest allocations by IPHC Regulatory Area using eLandings data that include the harvest location. While the community impact assessment is currently limited to Alaska, the feasibility of improving the model resolution for other regions is under investigation.

The use of this application can be guided by the PHMEIA app manual.

FINAL REMARKS

The PHMEIA model fosters a better understanding of the scope of regional impacts of the Pacific halibut resource. Leveraging multiple sources of socioeconomic data, it provides essential input for designing policies with desired effects depending on regulators’ priorities. By tracing the socioeconomic impacts cross-regionally, the model accommodates the transboundary nature of the Pacific halibut and supports joint management of a shared resource, such as the case of collective management by the IPHC. Moreover, the study informs on the vulnerability of communities to changes in the state of the Pacific halibut stock throughout its range, highlighting regions particularly dependent on economic activities that rely on Pacific halibut. A good understanding of the localized effects is pivotal to policymakers who are often concerned about community impacts, particularly in terms of impact on employment opportunities and households’ welfare. Fisheries policies have a long history of disproportionally hurting smaller communities, often because potential adverse effects were not sufficiently assessed (Carothers, Lew, and Sepez 2010; Szymkowiak, Kasperski, and Lew 2019).

Understanding the complex interactions within the fisheries sectors is now more important than ever considering how globalized it is becoming. Local products compete on the market with a large variety of imported seafood. High exposure to international markets makes seafood accessibility fragile to perturbations, as shown by the covid-19 outbreak (OECD 2020). Fisheries are also at the forefront of exposure to the accelerating impacts of climate change. For example, a rapid increase in water temperature off the coast of Alaska in the mid-2010s, termed the blob, is affecting fisheries (Cheung and Frölicher 2020) and may have a profound impact on Pacific halibut distribution.

Integrating economic approaches with stock assessment and management strategy evaluation (MSE) can assist fisheries in bridging the gap between the current and the optimal economic performance without compromising the stock biological sustainability. Economic performance metrics presented alongside already developed biological/ecological performance metrics bring the human dimension to the IPHC products, adding to the IPHC’s portfolio of tools for assessing policy-oriented issues. Moreover, the study can also inform on socioeconomic drivers (human behavior, human organization) that affect the dynamics of fisheries, and thus contribute to improved accuracy of the stock assessment and the MSE (Lynch, Methot, and Link 2018). As such, it can contribute to research integration at the IPHC (as presented in the IPHC’s 5-year program of integrated research and monitoring 2022-26) and provide a complementary resource for the development of harvest control rules, thus directly contributing to Pacific halibut management.

Lastly, while the quantitative analysis is conducted with respect to components that involve monetary transactions, Pacific halibut’s value is also in its contribution to the diet through subsistence fisheries and importance to the traditional users of the resource. To native people, traditional fisheries constitute a vital aspect of local identity and a major factor in cohesion. One can also consider the Pacific halibut’s existence value as an iconic fish of the Northeast Pacific. While these elements are not quantified at this time, recognizing such an all-encompassing definition of the Pacific halibut resource contribution, the IPHC echoes a broader call to include the human dimension into the research on the impact of management decisions, as well as changes in environmental or stock conditions.

Cited works

Aslaksen, Iulie, Winfried Dallmann, Davin L. Holen, Even Høydahl, Jack Kruse, Mary Stapleton, and Ellen Inga Turi. 2008. “Interdependency of Subsistence and Market Economies in the Arctic.” in The Economy of the North. Statistics Norway.

Carothers, Courtney, Daniel K. Lew, and Jennifer Sepez. 2010. “Fishing Rights and Small Communities: Alaska Halibut IFQ Transfer Patterns.” Ocean and Coastal Management 53(9):518–23.

Cheung, William W. L. and Thomas L. Frölicher. 2020. “Marine Heatwaves Exacerbate Climate Change Impacts for Fisheries in the Northeast Pacific.” Scientific Reports 10(1):1–10.

Haener, M. K., D. Dosman, W. L. Adomowicz, and P. C. Boxall. 2001. “Can Stated Preference Methods Be Used to Value Attributes of Subsistence Hunting by Aboriginal Peoples? A Case Study in Northern Saskatchewan.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 83(5):1334–40.

Krieg, Theodore M., Davin L. Holen, and David Koster. 2009. Subsistence Harvests and Uses of Wild Resources in Igiugig, Kokhanok, Koliganek, Levelock, and New Stuyahok, Alaska, 2005.

Lynch, Patrick D., Richard D. Methot, and Jason S. Link. 2018. “Implementing a Next Generation Stock Assessment Enterprise: Policymakkers’ Summary.” NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-F/SPO-183.

OECD. 2020. “Fisheries, Aquaculture and COVID-19: Issues and Policy Responses.” Tackling Coronavirus (Covid-19).

Steinback, Scott R. and Eric M. Thunberg. 2006. “Northeast Region Commercial Fishing Input-Output Model.” NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NE 188.

Szymkowiak, Marysia and Stephen Kasperski. 2020. “Sustaining an Alaska Coastal Community: Integrating Place Based Well-Being Indicators and Fisheries Participation.” Coastal Management 1–25.

Szymkowiak, Marysia, Stephen Kasperski, and Daniel K. Lew. 2019. “Identifying Community Risk Factors for Quota Share Loss.” Ocean and Coastal Management 178:104851.

Wolfe, R. J. and R. J. Walker. 1987. “Subsistence Economies in Alaska: Productivity, Geography and Development Impacts.” Arctic Anthropology 24(2):56–81.

Wolfe, Robert J. 2000. Subsistence in Alaska : A Year 2000 Update.

Wolfe, Robert J. 2002. Subsistence Halibut Harvest Assessment Methodologies. Report Prepared for the National Marine Fisheries Service, Sustainable Fisheries Division. San Marcos, CA.

Zeller, Dirk, Shawn Booth, and Daniel Pauly. 2006. “Fisheries Contributions to the Gross Domestic Product: Underestimating Small-Scale Fisheries in the Pacific.” Marine Resource Economics 21(4).